After reading my joint review of Stations of the Elevated and Style Wars, Tony, a longtime friend of mine, asked me a very good question (I bet you thought I forgot about it!). After assuring me that he understood my stance on graffiti and street art, and the importance of various artistic modes of expression, he asked where we should draw the line between self-expression and vandalism. This question actually made me pause, because I didn’t have a good answer that didn’t make me sound like an anarchist trying to overthrow the government or a complete hippie who believed that we should just do what makes us happy, man.

With illicit forms of self-expression, it’s hard to logically explain why I’m such a proponent when clearly it’s both illegal and will need to be removed at the taxpayer’s/owner’s expense. Especially now, as I am training to be a conservator (and taking a masonry conservation/architectural restoration course), I find it more and more difficult to justify my passion for an inherently illegal and aesthetically damaging mode of expression to my colleagues.

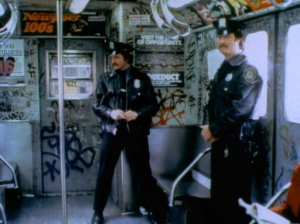

Growing up in New York City, I was exposed to both murals and graffiti. However, as a child, it never occurred to me that the artists who created these beautiful works had never gotten permission to paint on the walls that they covered. Even then, I abhorred toys and tags, thinking that they were childish attempts at self-glorification. When I first started this blog, I wanted to draw a line between street art and graffiti and stay as far away from the subject of graffiti as possible, instead sticking with the works resulting from the street art scene (hence the name of this blog), as these were the more “acceptable” and usually more “artistic” form of guerrilla art.

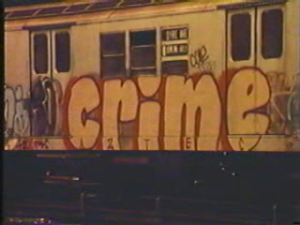

But, as I started researching the roots that street art had in graffiti, my understanding of graffiti’s history and culture evolved, and so did my acceptance. Not only did I come to accept and appreciate graffiti as a valid form of urban expression, I came to look for it in my own life and love its presence as well. The truth is that my dialectic has been based on a constantly evolving personal opinion about the importance and significance of how these guerilla acts of expression affect our urban visual landscape. Now, I want to differentiate between graffiti artists (those who create elaborate burners) and tagger/toys writers (who typically practice aerosol scrawl), even though I feel that their presence is still a significant mark upon the urban visual landscape (even if for the sheer reason of “brand name” recognition), I think that it is no more than a self-absorbed indulgence by disenfranchised or egotistical youth rather than artistic expression. So I suppose that tagging and sticker slapping is now where I draw the line in terms of urban guerilla modes of expression that I am not a proponent of.

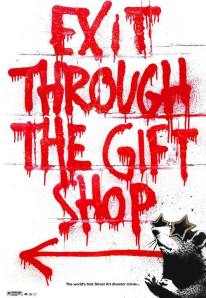

So, even though my opinion is constantly evolving the more I learn and am exposed to, I think that ultimately taggers and sticker slappers must learn some form of restraint. Gone are the days of “more is better” and the irony of being a ubiquitous brand name is dated. Now, graffiti artists are experiencing the pressure of being just that: artists. But as we push for legality as a means of justification for illicit forms of self-expression, a different question is raised, which is that of legitimacy. Does taking the illicit out of an inherently illicit form of urban artistic expression affect the authenticity of the artwork?

Artists like Swoon, who work with inherently ephemeral materials face less controversy and public animosity specifically because the works they put up are made of ephemeral materials. As I have written previously, Swoon’s prints can most frequently be found in the forgotten corners of otherwise obvious public spaces. She does not consider what she is doing illegal, and instead pastes her prints up unabashedly, sometimes in the middle of the day, which allows passersby to interact with her as she is hanging them. In spite of this impermanent aspect of her work, is it classified under the same category as permanent defacement of property and is still considered as illegal as art made with more permanent materials, such as aerosol spray or markers. Even street artists who work with less ephemeral materials, face less scrutiny than graffiti artists, if simply because what they do oftentimes just seems more artistic. This degree of acceptance is less felt towards graffiti artists, even if what they put up are artistic burners (which do require a lot of skill). This could be because of the remaining anti-graffiti sentiment resulting from the late 1980s, when former NYC mayor Ed Koch argued the Broken Window Theory in order to promote stricter anti-graffiti laws.

When UK artist Hush was in New York City during his weekend debut exhibition “Found” at the Angel Orensanz Foundation back in November, I ran into him by way of crazy random happenstance as I was out and about searching for some of the other work he had put up on buildings around downtown Manhattan (seriously, it’s a good story, you should ask me about it sometime). Once introduced, we got to chatting for about half an hour about his experiences and the whirlwind time he was having in NYC while I desperately tried to repress my desire to hop around squealing like a fan-girl. When we started talking about the issue of authenticity and whether showing in a gallery would de-legitimize his work, Hush said, “people ask me that all the time. I don’t think that it needs to be criminal to be authentic. Sometimes I’ll feel naughty and pull out a pen and tag something up, but I rarely do anything illegal. I’m not a criminal. It’s not like I ruin property- I revitalize areas that are already ignored and wrecked.” And indeed, Hush had gotten permission from the three locations that he had put up his work up outside the gallery.

And his is a sentiment I can get behind. I think to justify an inherently illegal act, it is the first instinct of the connoisseur to frame these works and put them into a gallery or cut them from the wall and auction them to the highest bidder. Many argue that removing a form of expression so closely tied with the urban environment and putting it into a stark white setting undermines the legitimacy of the piece by destroying its context. However, like Hush, I do not believe that this is the case. In recent years, as graffiti has started to become recognized as a legitimate form of artistic expression, and as street art (as I mentioned before, the “third generation graffiti”) has coming into prominence, it is more common for artists to seek permission, take part in legal exhibitions, or show their work in galleries. Even public opinion has started to ease up somewhat in regards to this form of expression.

I have previously written about the revitalization of third spaces (areas clearly owned but otherwise unkempt), the rationale of making art available everywhere everyday to everyone, and the importance of reclaiming the urban landscape from the corporate machine. Permission is sometimes obtained for murals and more complex and artistic-looking graffiti. However, whether due to the aversion of the public to accept graffiti as an authentic means of artistic expression or to the aversion of grafiteros to find legal alternatives or the futility of attempting to separate urban art from the urban situation that it usually arises out of in the first place, permission is not usually granted or even asked for.

Once it is understood that legality is necessary to legitimize this body of work, the main concern becomes authenticity. After all, separating these pieces from the environments that spawned them and putting them into sterile environments that may destroy the intent of the work becomes a worry. However there is another alternative available for consideration. In fact, I think that a true solution for both these issues can come from grafiteros asking permission to practice their craft as well as through the generation of legal projects and creation of more legal spaces to work on.

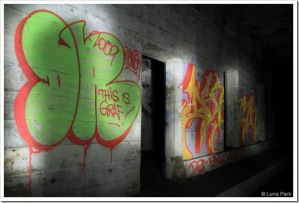

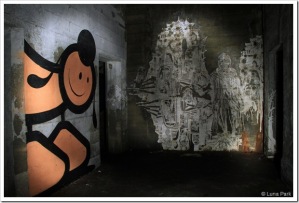

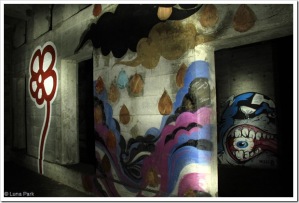

Legal walls and spaces have been around for as long as graffiti has been in existence, though it is important to check if the location is curated and requires a submission for consideration or only open to locals. Two very interesting sites have worked to document the legal wall spaces around the world and the USA. I have seen and experienced a variety of spaces, from mutually understood spaces for street art, such as Wooster Street, closed wall spaces, such as the 106 Street Wall of Kings, institutions showcasing multiple artists’ works, such as 5 Pointz and ABC No Rio, institutions that offer outdoor space to one artist at a time, such as Deitch and Woodward Gallery, and institutions that have exhibited the works of street artists in interior spaces, such as 112 Greene Street and Angel Orensanz Gallery (to name only a few of each!), as well as the host of privately and public owned walls that have proudly exhibited murals and artists’ works. Additionally, organizations such as No Longer Empty work to revitalize third spaces with artwork and make art available to a wider public by connecting owners of derelict spaces with artists. Each type of space has its pros and cons, but I think that it is important to have these types of spaces for artists and writers to exhibit their work on.

So in the end, I suppose the best argument I can come up with is that since graffiti is here anyway, why not embrace it and push for legal spots rather than relegating it to the rooftops and alley, or worse, the starkness of an institutionalized space? No matter what, I remain a proponent for the legitimization of this urban form of artistic expression and will continue writing in my own attempt to legitimize this form of urban outsider art as a well-received and widely-recognized form of artistic expression. Therefore, I strongly urge artists and writers to keep expressing their creativity, but to ask owners for permission or seek legal projects. By moving this form of urban expression to the light of day, we can work to legitimize this beautiful art together.