I first heard about Banksy’s film Exit Through the Gift Shop earlier this year, when it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in February. I was really excited to watch it because I was sure it would provide a glimpse into the life and thought process of the incredible infamous and equally elusive British street artist Banksy, whose works have appeared everywhere from his native city of Bristol to the wall that divides Israel and Palestine. His repertoire does not just include stencils and spray but playful installations and elaborate hoaxes. In fact, in 2009, he gained additional notoriety by pirating the walls of a public Bristol museum, where he hung his own artworks and captions, as well as through his dolphin ride installation, which had been done in response to BP’s oil spill. Most recently, he has even been credited with directing the opening sequence of the October 11, 2010 episode of The Simpsons.

But this is not a post about Banksy, nor is this a film about Banksy. “What?” you may ask, incredulously, “but it’s A Banksy Film!” At first, I was a little disappointed too, but to be honest, viewers knew that this would be the case fairly early on, when a hooded Banksy with altered voice gave a brief introduction to the film. Think of this film more as a Banksy project, if that helps you wrap your head around the massive amounts of disappointment that I’m sure you’re feeling right now. But take solace in the fact, dear reader, that although Banksy and his own art appear only sporadically throughout the film, Exit Through the Gift Shop still serves as a wonderful introduction into the world of street art, and its message makes this film a prime example of a Banksy project.

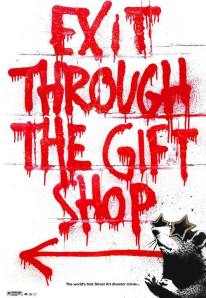

So yes, although this film was not what I had originally expected, it was still incredibly enjoyable and informative. Aptly termed “the world’s first street art disaster movie,” it definitely provides a rather candid glimpse into the nocturnal adventures (both failed and successful) of a variety of street artists. Aside from Banksy, big names such as Space Invader, Monsieur Andre, Zeus, Shepard Fairey, Neckface, Sweet Toof, Ron English, Dotmasters, Swoon, Borf, Buffmonster and their works all made appearances in the film. And although it was a movie originally intended to be about street art and Banksy, it soon becomes quite clear how and why it developed into a documentary about the eccentric man behind the camera.

Meet Thierry Guetta, a French ex-pat living in Los Angeles, who ran a vintage clothing store and developed the rather peculiar obsession of filming absolutely anything and everything on his camera. While on holiday in France, he began filming the work of his cousin, street artist Space Invader and was soon drawn into the burgeoning street art scene. Upon returning to L.A., he continued seeking out the rising stars of the street art scene, a process that was aided greatly by his cousin, then by Shepard Fairey, who though reluctant at first, accepts Guetta as first a tagalong who happens to have a camcorder and then lookout on his nighttime wanderings. Guetta dives into his role with enthusiastic incompetence and films everything with a blundering sense of awe. His filming, finally having been given the direction and focus that it had previously lacked, leads Guetta to inadvertently take up the task of documenting this ephemeral genre of contemporary art.

Eventually, Guetta develops a desire to meet the infamous Banksy, an artist who he believes will complete his comprehesive record of street artists. Fate somehow brings Banksy to the West Coast, and Shepard Fairey introduces him to Guetta, who has developed the reputation of the man for out-of-town street artists to contact to get everything from supplies to information on the best walls to a nighttime ride. Soon Guetta is faithfully shadowing the elusive Banksy, even traveling with him to England to record his workshop and capture his projects.

Spoiler alert!! For those of you who want to find out for yourselves how this movie unfolds, and are only interested in the critical review and analysis, please skip ahead to the paragraph after the Life is Beautiful wall picture!

Meanwhile, inspired by the works of the artists around him, and eager to take part in what looked like a good time, it is revealed that Guetta has started experimenting with the mass dissemination of images via stickers and wheat-pasting under the psuedonym Mister Brainwash (MBW) and it comes to light that Thierry Guetta had been accumulating thousands of hours of footage with no real intention of editing it together to create a comprehensive documentary. Meanwhile, Banksy is preparing for his big debut show in L.A., Barely Legal. After this monumental US show, the commercial market for street art in contemporary art collections started to boom. It was at this time that Banksy decided that the time was right to show the world that street art was a messy business and that it had never been about the money. Faced with Banksy’s challenge to finally create a film, Thierry Guetta finally starts to edit his accumulated tapes.

Six months later, Guetta flies to London to show Banksy his almost-complete film, Life Remote Control. Banksy is absolutely flabbergasted and slightly terrified with the result, saying that the film was like someone with ADHD had gotten a hold of a remote control and was flipping through TV channels for 90 minutes. Keeping the tapes in an attempt to create a more complete and accurate documentary which would better portray the importance of street art as captured by Thierry Guetta, Banksy gives Guetta an assignment designed to distract: go home to L.A., create some art, and put on a show.

Thierry Guetta throws himself into this project, fully adopting the MBW persona, and invests in a production line of artists and assistants, working to churn out prints of altered pop culture icons in a thoroughly Warhol-esque manner (but with none of the Warhol irony). Eager to please Banksy, MBW excitedly prepares for his huge gallery debut, appropriating a huge studio for installations, prints, and other assorted projects. Meanwhile a change is occurring in this central character: the blundering but otherwise endearing Thierry Guetta slowly transforms into an art world douchbag. Constantly on his cell phone, he becomes concerned mostly with hype, and attempts to become the biggest and hottest commodity in L.A. He sells pieces ahead of the show with arbitrary price tags, most of which are dependent on the object’s size, and often in the tens of thousands of dollars. Hours before the show he transforms into a control freak who is concerned with only interviews and handshakes. But despite the massive amounts of disorganization and procrastination, manages to pull off a critical success of a show that is attended by thousands of people. After the exhibition, he appears arrogant and self-satisfied, pleased to have finally established his place among the legendary street artists he had been filming for the past decade. Meanwhile, Banksy and Shepard Fairey show a certain amount of disdain for the pointlessness of MBW’s art, and seem uncertain as to what to make of the public sensationalism surrounding MBW.

Directed and produced by a notorious and mysterious trickster, this film has been widely called nothing more than an elaborate hoax, and has even been classified as a “prankumentary” by New York Times film critic Jeanette Catsoulis. I personally disagree with her assessment because it’s absolutely possible for someone to fall into a career over the course of a year and a half and create massive amounts of art when they’ve hired a production line of assistants. Some have even speculated that MBW was created for the purpose of the documentary. But the question as to whether or not Exit Through the Gift Shop is a case of life following art or art following life is irrelevant, because it’s the introduction and message that’s important.

The first act of Exit Through the Gift Shop is a documentary about street art, as seen through the exuberant eyes of Thierry Guetta, and the second act of this film becomes a documentary about Guetta as MBW. MBW becomes the perfect juxtaposition for street artists like Shepard Fairey, who has spent years finding his style, and Banksy, who is very thoughtful with his projects. While most artists spend their time developing their technique, finding their style, and thinking about the meaning of their works, MBW found his style quite quickly and almost accidentally, and uses repetition and gigantism without too much thought. Interviews taken during MBW’s debut exhibition show viewers praising the work as revolutionary, and assigning value to objects that clearly have none.

So perhaps this film isn’t so much a documentary, but more of an exposé. More than that, this film highlights the relationship between the world of street art and the world of contemporary/pop art in its second act. With a note of irony that only street artist can provide, this film raises questions regarding issues such as the monetary valuation of artwork, the commercialization of street art, and the appropriation of images. Perhaps most interestingly, Exit Through the Gift Shop underscores the pretentiousness of the contemporary art scene. So yes, this film makes you think. And, more than that, it successfully does what it was meant to do: provide the viewer with a glimpse into the chaotic world of street art and give them a good time while doing it.

Exit Through the Gift Shop will be digitally available for both rent and purchase on iTunes and Video on Demand channels beginning November 23, 2010 and available on DVD (with awesome extras, like a version of Life Remote Control) on December 14, 2010. I definitely suggest watching this film with some friends, not just because it raises a lot of quite interesting questions and topics that you’ll most likely want someone to talk to, but because it’s just that good of a ride. And the best part is that you don’t need to be a street art buff to love this movie. For all my analysis, it’s simply a great introduction into the world of street art, and just a lot of fun to watch.

For those of you who want more background on the film, here’s a wonderful interview with the producer and editor of Exit Through the Gift Shop with Movie City News about the documentary that never really existed. And, here‘s an interesting interview with Shepard Fairey about the film as well.